Scientific Doors, Speciation happens when one group of living things splits into two or more separate groups that can no longer produce young together. Scientists estimate that 8.7 million species exist on Earth today, yet only 1.2 million have been named and studied. Each of these groups formed through complex processes that took thousands or millions of years.

How does a single population become completely different groups? This natural process drives the emergence of biodiversity across every continent and ocean. Without it, life would remain frozen in one form forever.

Research shows that environmental triggers for evolution play a massive role. From tiny insects to large mammals, every living thing carries marks of this ancient pattern. This article reveals how nature builds new life forms through proven scientific methods.

A Simple Start to Speciering and How Nature Shapes New Lines of Life

Understanding what drives populations to diverge requires looking at both historical observations and modern genetic evidence. The mechanisms work across all living things, from microscopic bacteria to massive whales.

What Speciering Means in Plain Words

The term describes how populations diverge until they become distinct biological units. When groups stop sharing genes, they follow separate paths. Over time, physical traits, behaviours, and internal systems become so different that breeding becomes impossible.

Think of it as a biological branching point. One population faces new pressures, adapts, and eventually loses compatibility with the original group. This split marks the birth of something entirely new.

Why This Idea Matters in Nature and Science

Natural species formation explains the tremendous variety we see today. From desert lizards to deep-sea fish, each organism reflects millions of years of accumulated changes. Understanding these mechanisms helps scientists predict how groups respond to environmental shifts.

Medical research benefits too. Studying how bacteria and viruses change helps teams develop better treatments. Agricultural experts use these principles to breed stronger crops. The same patterns that create wild species also inform human innovation.

How Natural Species Formation Links with Long-Term Change

Small modifications build over generations. A slightly longer beak helps one bird access hidden food. That bird survives, breeds, and passes the trait forward. Multiply this across thousands of generations, and entire body structures transform.

Mountains rise, rivers change course, and climates shift. Each alteration pushes populations in new directions. Gradual evolutionary change rarely happens at uniform speeds. Sometimes groups remain stable for ages, then rapid shifts occur when conditions demand it.

Short Early History of How Thinkers Shaped the Idea

Charles Darwin observed variations during his Galápagos voyage in 1835. He noticed finches with different beak shapes on separate islands. Each type matched the available food sources perfectly. This observation planted seeds for his later work.

Ernst Mayr refined these concepts in the 1940s. He emphasised reproductive isolation as the defining moment. When two groups can no longer produce fertile offspring, the split becomes permanent. Modern scientists build on these foundations using genetic tools Darwin never imagined.

Many people wonder what a simple definition of this process would be. At its most basic, it occurs when populations become reproductively isolated and develop into distinct groups that cannot interbreed successfully. This biological separation marks the point where one becomes two.

Early Steps That Push Groups Apart in the Wild

Natural barriers and environmental pressures create the initial conditions for populations to follow separate paths. These early stages set the foundation for all later divergence.

Geographic Breaks That Separate Groups

Physical barriers create the first splits. A river changes path and divides a forest. Suddenly, squirrels on one side never meet squirrels on the other. Each group faces different predators, foods, and weather patterns.

The Grand Canyon separated ground squirrels roughly 5 million years ago. Today, Kaibab squirrels live only on the north rim, while Abert’s squirrels inhabit the south rim. Their fur colours and tail patterns differ noticeably. This demonstrates how environmental triggers for evolution work through simple separation.

Small Shifts in Land or Climate That Lead to New Paths

Ice ages repeatedly split animal populations across Europe and Asia. During cold periods, forests shrank into isolated pockets called refugia. Groups survived in these small zones for thousands of years. When ice retreated, populations expanded but often remained distinct.

Studies of European grasshoppers reveal at least 20 genetic lineages formed during these cycles. Each refugium produced slightly different traits. Some developed longer wings for dispersal; others evolved stronger jaws for tougher vegetation.

Food Sources and Living Spaces That Place Pressure on Groups

Competition drives adaptation quickly. When food runs short, individuals with advantageous traits survive better. Cichlid fish in African lakes show this pattern dramatically. Over 1,500 species evolved in Lake Malawi alone, most within the last million years.

Different cichlids specialised in scraping algae, crushing snails, or hunting smaller fish. Each feeding style required specific jaw structures and teeth patterns. Groups that mastered different foods stopped competing directly and drifted apart genetically.

How Adaptive Traits Formation Starts Inside Small Groups

Random variations appear constantly through genetic mutations. Most changes bring no benefit, but occasionally one proves useful. A beetle develops thicker armour that protects against new predators. That beetle survives longer and produces more offspring carrying the protective trait.

The peppered moth in England offers a classic example. Before industrial pollution, light-colored moths dominated. As soot darkened trees, dark moths gained camouflage advantages. By 1895, dark forms made up 98% of the Manchester population. Selection pressure completely flipped the colour balance within decades.

Scientists often ask about the four stages that mark this progression. The sequence includes population separation, genetic divergence through independent Speciering and evolution, development of reproductive barriers, and complete reproductive isolation, preventing gene flow. Each stage builds on the previous one.

When Genes Move in New Directions During Speciering

Genetic changes form the molecular foundation of all biological divergence. Understanding DNA-level shifts helps scientists trace relationships and predict how populations will respond to pressures.

How Tiny Gene Changes Add Up Over Time

DNA mutations occur constantly in every living cell. Most stay neutral, causing no visible effect. However, when populations separate, different mutations accumulate in each group. A change that helps survival in one area might harm organisms in another location.

Scientists compared wolf and dog DNA to measure this drift. Despite only 15,000 to 40,000 years of separation, dogs show significant genetic differences. Domestic breeds carry mutations affecting digestion, behavior, and appearance that wild wolves lack entirely.

Role of Genetic Drift and Founder Events

Small populations magnify random chance. If only ten individuals colonise a new island, their genes represent a tiny sample of the original population. Missing variations never return without new arrivals. This “bottleneck effect” shapes the evolutionary development process dramatically.

Mauritius once hosted the dodo bird. These flightless birds descended from pigeons that reached the island centuries earlier. Isolated from mainland populations, they grew larger, lost flying ability, and developed unique traits. The founder event limited genetic diversity from the start.

What Reproductive Barriers Look Like in Nature

Physical incompatibilities prevent mating. Flowers evolved different tube lengths matching specific pollinator tongues. Short-tubed flowers serve bees, while long-tubed varieties attract moths. This specialization keeps pollen transfer separate.

Behavioural barriers work equally well. Many birds rely on specific songs or displays. If one population develops a new song pattern, outsiders won’t recognise it as a mating signal. Fireflies flash in species-specific patterns. Wrong timing or colour means no response from potential mates.

Notes from Taxonomy Research Insights Used by Scientists

Modern geneticists sequence entire genomes to trace relationships. DNA analysis revealed that African elephants actually comprise two distinct species: forest and savanna types. External appearances looked similar, but genetic evidence showed separation occurred 2.5 million years ago.

Museums preserve tissue samples from thousands of specimens. These archives let researchers compare historical and modern populations. Temperature records, habitat photos, and collection dates provide context for understanding how groups changed.

Researchers frequently examine what most commonly drives this process. Geographic isolation represents the primary cause, occurring when physical barriers prevent gene flow between populations that then evolve independently. This pattern appears across continents and climate zones.

Main Types of Speciering Seen Across Nature

Different pathways produce the same result through distinct mechanisms. Recognizing these patterns helps scientists understand which forces shaped specific groups.

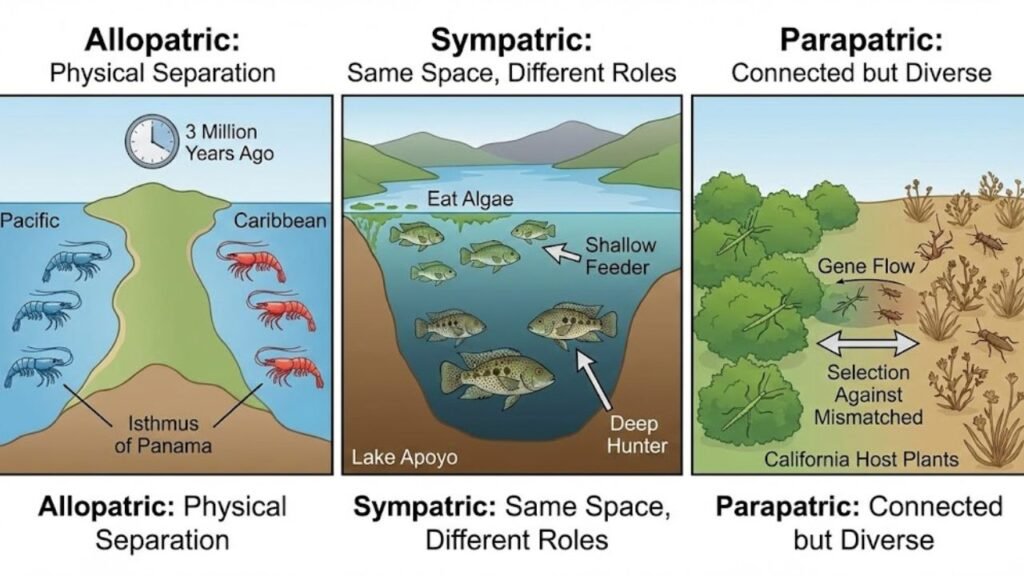

Allopatric Steps Shaped by Land Divides

This pattern requires complete physical separation. The Isthmus of Panama formed roughly 3 million years ago, splitting marine environments. Shrimp species on the Pacific and Caribbean sides now show distinct differences. Scientists identified 15 sister species pairs, each split matching the land bridge timing perfectly.

Mountain ranges create similar barriers. The Himalayas separated bird populations across Asia. Groups on the southern slopes face monsoon rains, while northern populations endure harsh continental climates. These different pressures drove divergence even in closely related species.

Sympatric Paths Formed Inside the Same Space

Groups split without physical barriers through specialisation. Cichlid fish in Nicaragua’s Lake Apoyo demonstrate this pattern. One ancestral species gave rise to two forms living in the same waters. One type feeds in shallow areas, eating algae, while the other hunts in deeper zones.

Speciation patterns in nature like this seemed impossible until genetic evidence proved otherwise. The split happened within the last 10,000 years, making it one of the fastest documented cases. Preference-based selection drove the change as females preferred mates with specific colours matching their feeding zones.

Parapatric Patterns Shaped by Changing Borders

Populations remain partially connected but experience different conditions across their range. The walking stick insect Timema cristinae in California shows this pattern. Populations on different host plants developed distinct colour patterns for camouflage.

Gene flow continues at a low level where plant types overlap. However, strong selection against mismatched individuals maintains differences. Insects on the wrong plant get eaten more often. This ecological influence on species creates reproductive isolation despite physical contact.

Peripatric Lines Formed by Very Small Groups

A few individuals colonize new territory at the edge of their range. This tiny founding population carries limited genetic variation. Strong selection in the new environment rapidly reshapes the group.

Hawaiian honeycreepers illustrate this pattern beautifully. A single finch-like ancestor reached the islands millions of years ago. Descendants spread across different islands and habitats. Today, over 50 species exist, each with specialised beak shapes. Some evolved curved bills for nectar feeding, while others developed parrot-like beaks for crushing seeds.

People often request specific examples showing these mechanisms in action. Five excellent cases include Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands, cichlid fish in African lakes, Kaibab and Abert’s squirrels at the Grand Canyon, Hawaiian honeycreepers, and London Underground mosquitoes, which adapted to subway environments within 150 years.

Traces of New Groups Seen in Living Creatures and Old Stones

Evidence from both living organisms and fossil records documents how populations transformed through time. These examples span millions of years and demonstrate universal principles.

Darwin’s Finches and How Their Traits Changed

The Galápagos Islands host 14 finch species, all descended from a single mainland ancestor. Each species evolved distinct beak shapes matching available food sources. Ground finches crush hard seeds with deep, powerful beaks. Cactus finches probe flowers with long, pointed bills.

Peter and Rosemary Grant studied these birds for over 40 years. During a 1977 drought, they documented rapid selection for larger beaks. Birds with bigger beaks cracked tough seeds that others couldn’t access. The average beak size increased measurably in just one generation.

African Cichlids and Quick Branching Events in Lakes

Lake Victoria holds over 500 cichlid species, most of which evolved in the last 15,000 years. This explosion of diversity happened faster than almost any other documented case. Different species evolved varied feeding strategies, body shapes, and colour patterns.

Jaw mechanics vary dramatically among types. Some possess pharyngeal jaws specialized for processing algae. Others developed forward-facing teeth for ripping scales off other fish. This rapid species differentiation science demonstrates how environmental opportunity speeds up the process.

Bears That Moved Apart Over Time

Brown bears and polar bears split roughly 500,000 years ago. As ice sheets expanded, some brown bears adapted to Arctic conditions. They developed white fur for camouflage on sea ice, smaller ears to reduce heat loss, and different fat metabolism.

Genetic studies reveal that occasional interbreeding still occurs where ranges overlap. Hybrid “grizzly-polar” bears appear in Canadian Arctic regions. However, the two groups maintain distinct populations because their behaviours and habitats differ so greatly.

Orchids and Small Shifts That Formed New Kinds

Orchid diversity exploded alongside insect pollinators. Many species evolved flowers matching specific bee, moth, or fly characteristics. Flower shape, colour, and scent create barriers between species. Over 25,000 orchid species exist today, making them one of the largest plant families.

Some orchids mimic female insects so convincingly that males attempt mating with the flowers. During these efforts, pollen attaches to the insect’s body. This deceptive strategy ensures pollen reaches the right flower type while preventing cross-pollination with unrelated species.

How Fossil Layers Show Gradual Evolutionary Change

Palaeontologists trace lineages through sedimentary rocks. Horse evolution provides excellent documentation. Early horses stood only 0.4 metres tall with multiple toes. Over 55 million years, horses grew larger, developed single hooves, and evolved teeth suited for grazing.

Trilobite fossils reveal similar patterns. These ancient marine arthropods dominated oceans for 270 million years. Over 20,000 species appeared during that span, each adapted to specific depths, temperatures, and food sources. Extinction events cleared space for new types to emerge.

When examining the most recent documented cases, Italian wall lizards introduced to Pod Mrčaru Island in 1971 stand out. Within just 30 generations, they developed distinct gut structures and head shapes adapted to their new environment. This rapid transformation shows how quickly populations respond to novel conditions.

How People Shape Speciering Without Even Noticing

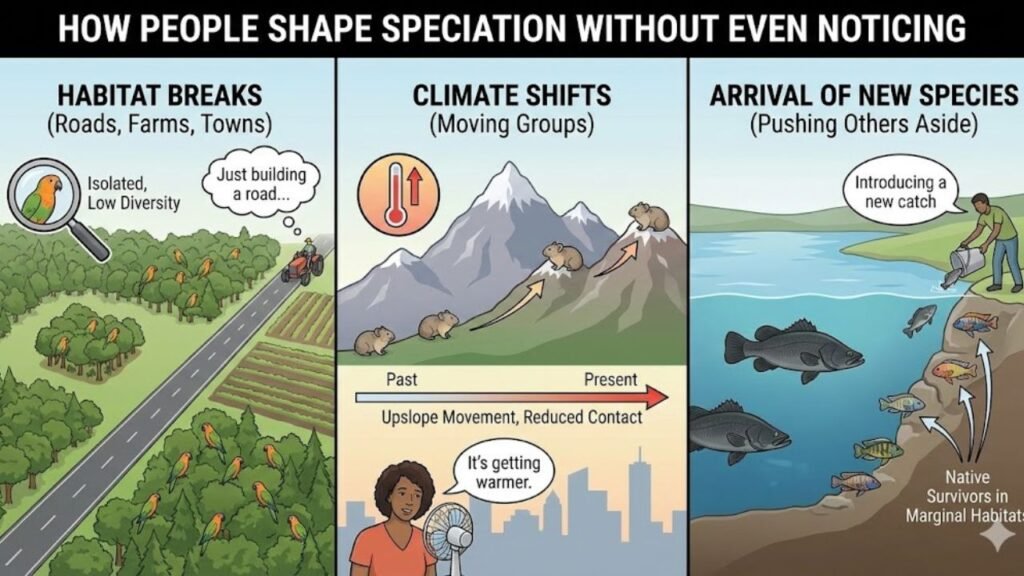

Human activities now influence biological divergence at unprecedented scales. Roads, farms, cities, and climate change reshape evolutionary pathways across the planet.

Habitat Breaks Made by Roads, Farms, and Towns

Human development fragments wild spaces into isolated patches. Roads slice through forests, preventing animal movement between fragments. Orange-bellied parrots in Australia now survive in only a few coastal areas separated by agriculture.

Less than 250 individuals remain in the wild. Each isolated group faces a higher inbreeding risk. Small populations lose genetic diversity quickly. Scientists worry these fragments may develop into distinct lines before conservation efforts reconnect them.

Climate Shifts and How They Move Groups

Rising temperatures push species toward cooler regions. Mountain-dwelling animals climb higher as the lowlands warm. Pikas in North American mountains moved upslope 145 metres in recent decades. Groups on different peaks now experience reduced contact.

Coral reefs face similar pressures. Warming oceans force heat-sensitive corals into deeper or polar waters. Populations that once formed continuous networks now exist as separated clusters. This fragmentation accelerates biodiversity emergence of locally adapted forms.

Arrival of New Species That Push Others Aside

Introduced species disrupt native populations dramatically. Nile perch introduced to Lake Victoria devastated native cichlid populations. Over 200 endemic species vanished within decades. Survivors occupy marginal habitats where perch rarely venture.

Competition for resources forces native groups into narrow specialisations. This pressure can speed divergence as populations adapt to avoid introduced competitors. However, many species lack time to adapt and simply disappear.

Conservation and Taxonomy Link in Helping Fading Groups

Protected corridors help separate populations reconnect. Wildlife bridges over highways let animals cross safely. Research in Europe shows these structures work. Genetic diversity increases when populations exchange individuals regularly.

Captive breeding programmes preserve genetic material from shrinking populations. San Diego Zoo’s frozen zoo stores tissue samples from thousands of rare animals. If wild populations vanish, scientists can potentially restore them using preserved genetics. This work requires accurate new species identification to ensure proper matches.

Many wonder whether humans themselves represent an example of this process. Humans are indeed a product of past events, but currently exist as one species with no reproductively isolated populations despite geographic variation. Another common question asks whether new species are being created. Yes, they continue forming through natural processes, though human activities accelerate some pathways while preventing others through habitat destruction.

Science Fields That Use Speciering Ideas in Daily Study

Research teams across multiple disciplines apply these principles to solve practical problems. The concepts extend far beyond basic biology into medicine, agriculture, and environmental management.

Notes from Species Differentiation Science in Modern Labs

Geneticists track mutations to build evolutionary trees. Comparing DNA sequences reveals how closely related different groups are. The human genome shares 98.8% similarity with chimpanzees, confirming common ancestry roughly 6 million years ago.

Laboratory evolution experiments compress timescales. Bacteria reproduce in hours, allowing scientists to watch changes across thousands of generations. Richard Lenski’s E. coli experiment began in 1988. After over 75,000 generations, bacteria evolved completely new metabolic abilities, including processing citrate under aerobic conditions.

Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” Theodosius Dobzhansky, geneticist who helped merge evolutionary theory with genetics

The rate of evolution is not constant. Short bursts of rapid change are separated by long periods of stability.” Stephen Jay Gould, palaeontologist, describing punctuated equilibrium

Ecological Influence on Species During Long-Term Change

Field biologists document how communities shift together. When woodpecker populations declined in California oak woodlands, acorn-eating insects exploded. This cascade affected tree health and other bird species. Understanding these connections helps predict which groups face pressure during environmental shifts.

Predator-prey relationships drive rapid adaptation. Guppies in Trinidad streams show different patterns based on predator presence. High-predation streams favour small, dull-colored males that mature quickly. Low-predation streams support larger, brighter males. This demonstrates how ecological influence on species operates in real time.

Speciering Patterns in Nature Seen in Today’s World

Island systems provide natural laboratories. New Zealand’s flightless birds evolved without mammalian predators. Kiwis, kakapos, and takahe all lost flight ability after arriving on predator-free islands. This parallel evolution demonstrates how similar conditions produce similar results.

Madagascar’s lemurs show explosive radiation. Over 100 species evolved from a single ancestor that reached the island roughly 20 million years ago. Ecological opportunities on this isolated landmass drove rapid diversification into varied ecological roles.

Speciering in Chemistry and How Forms of Elements Shift

The term extends beyond biology. Chemists use “speciation” to describe how elements exist in different chemical forms. Mercury appears as elemental metal, inorganic salts, or organic compounds like methylmercury. Each form behaves differently in the environment and affects living things uniquely.

Understanding chemical speciation helps track pollution. Different forms require different treatment methods. This cross-disciplinary connection shows how one concept illuminates multiple scientific fields.

How New Species Identification Helps Environmental Teams

Accurate classification guides conservation priorities. Groups once thought common sometimes split into multiple rare species. The African elephant example revealed two species instead of one. This changed protection strategies significantly as forest elephants face different threats than savanna types.

DNA barcoding speeds identification dramatically. Scientists sequence a standard gene region from unknown specimens and compare it against reference libraries. This technique identified cryptic species in mosquitoes, helping disease control teams target the right vectors.

Questions about whether inbreeding leads to this process arise frequently. Inbreeding reduces genetic diversity but doesn’t directly cause divergence. However, small inbred populations may experience genetic drift that contributes to separation when combined with isolation.

Key Comparison: Modes of Speciering

| Type | Barrier Required | Time Frame | Example |

| Allopatric | Complete separation | 100,000+ years | Grand Canyon squirrels |

| Sympatric | None | 10,000+ years | Lake Apoyo cichlids |

| Parapatric | Partial barrier | 50,000+ years | Walking stick insects |

| Peripatric | Edge isolation | Variable | Hawaiian honeycreepers |

Pulling All Threads Together for a Clear Picture of Speciering Today

Modern science reveals both the mechanisms and implications of how life diversifies. This knowledge guides conservation efforts and helps predict biological responses to environmental changes.

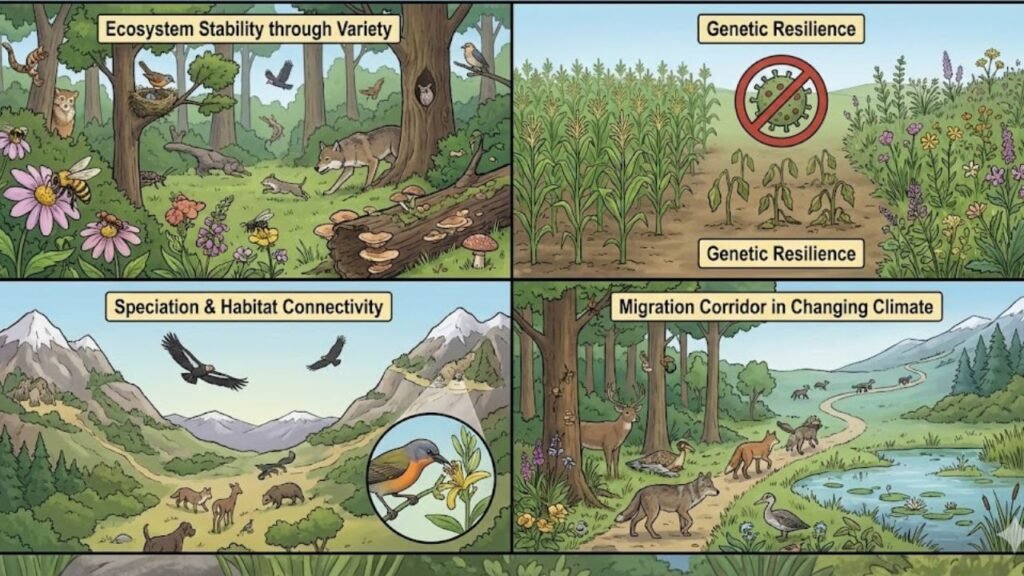

Why This Idea Matters for Biodiversity Emergence

Every ecosystem depends on variety. Different species fill unique roles in nutrient cycling, pollination, and predation. When diversity drops, system stability decreases. Understanding how biodiversity emerges helps scientists predict which communities face collapse.

Genetic diversity within species matters equally. Populations with broad genetic bases adapt better to changing conditions. Monocultures in agriculture demonstrate this principle negatively. One disease can devastate genetically uniform crops. Wild relatives provide genes for disease resistance precisely because they maintain variation.

How Speciation Mechanisms Help Protect Rare Groups

Knowing which pressures drove divergence informs protection strategies. Species formed through geographic isolation need habitat corridors. Groups that specialize in narrow ecological niches require protecting those specific resources.

California condors nearly went extinct, with only 22 individuals surviving in 1987. Careful management of the remaining genetic diversity helped rebuild populations. Today, over 500 exist, but genetic bottlenecks still limit their long-term health. This case shows how taxonomy research insights guide practical conservation.

How Natural Patterns Guide Conservation Steps

Protecting transition zones helps maintain evolutionary processes. Ecotones, where habitats meet, often host high diversity because they support species from both environments, plus specialists of the boundary itself. These areas serve as laboratories where new adaptations emerge.

Climate change will push many species into new ranges. Conservation planning must account for this movement. Protecting migration corridors and diverse habitats gives populations space to adapt rather than face extinction.

Also Read: LivPure Colibrim: Can a Liver Supplement Help You to Burn Fat and Boost Energy?

What Present Trends Hint at Later Stages of Study

Technology advances faster than ever. Portable DNA sequencers now operate in remote field camps. Scientists can identify species, track individuals, and measure genetic diversity without returning to labs. This speed helps monitor rapid changes in real-time.

Citizen science expands data collection dramatically. Apps like iNaturalist let anyone document wildlife sightings. Over 100 million observations exist in public databases. This crowdsourced information reveals distribution changes that would take decades for professionals to gather alone.

Some ask whether this process can be reversed. The process rarely reverses completely, but when reproductive barriers break down through habitat changes, previously separated groups may interbreed and merge into hybrid populations. History shows a few cases where once-distinct lines rejoined.

Others wonder who first named this concept. Orator F. Cook first used the term “speciation” in 1906 to describe the process by which new species originate. Ernst Mayr is often called the father of the field for his 1942 work defining biological species concepts and explaining isolation mechanisms.

Critical Factors in Successful Species Formation

- Environmental pressure ranks highest among drivers. Groups facing new stresses adapt or disappear. Strong selection accelerates change dramatically.

- Population size matters significantly. Small groups experience faster genetic drift. However, they also risk extinction before establishing themselves.

- Time requirements vary widely. Bacteria can speciate in years. Large mammals need millennia. Generation time determines the pace of genetic accumulation.

- Geographic barriers provide the clearest path. Physical separation prevents gene flow completely, giving populations freedom to diverge independently.

How Human Choices Now Steer the Path of Evolving speciering

This scientific process continues every day across the planet. Mountains rise, climates shift, and populations adapt or vanish. Understanding these natural patterns helps protect the remarkable variety of life surrounding us. Each species tells a story millions of years in the making, written in genes and shaped by endless environmental pressures. The same forces that created past diversity continue building tomorrow’s biological landscape.

Human actions now influence these ancient patterns at unprecedented scales. Whether we fragment habitats or restore connections, our choices shape which lineages survive and which paths remain open. Recognising how speciering works gives us the power to guide these processes wisely rather than accidentally destroying what took aeons to create.